The Cold War and the Birth of NATO

Video

The Cold War Begins

The Soviets Catch Up

After the Soviet Union conducted their first successful test of a nuclear weapon on August 29, 1949, the threat of future Communist aggression became a driving factor in developing NATO's military forces.

A 31 kiloton bomb tested on November 5, 1951 in Nevada

A strategy of 'deterrence' - having the power to retaliate with as much force as was used against you - would be followed to prevent war. This led to a nuclear arms race between the Soviets and the Americans, each trying to gain the advantage.

The World goes MAD

As the production of nuclear weapons proliferated, the USA and the Soviet Union had the capability to destroy the world more than 50 times over. The phrase "Mutually Assured Destruction" (MAD) was coined to describe this strategy.

(Robert Jervis,"The Dustbin of History: Mutual Assured Destruction," Foreign Policy website, November 9, 2009. *Click below to view website) The time-lapse video shows how extensive nuclear testing was throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

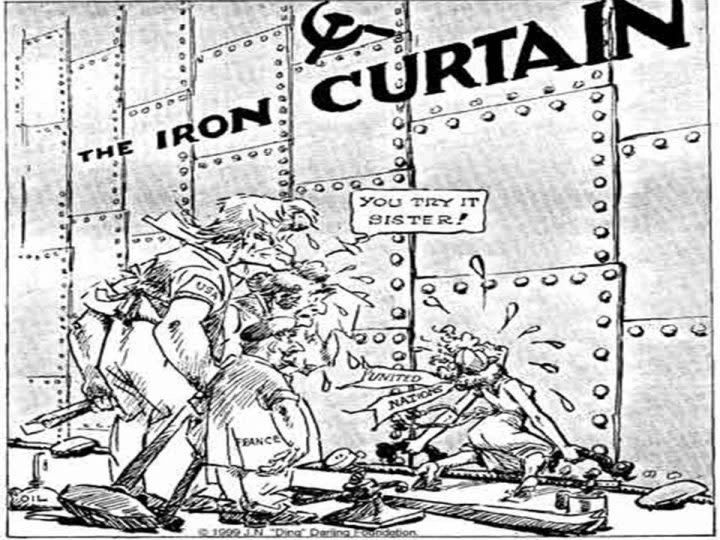

"Beware, I say, time may be short....A shadow has fallen upon the scenes so lately lighted by the Allied victory. Nobody knows what Soviet Russia and its Communist international organization intends to do in the immediate future, or what are the limits, if any, to their expansive and proselytizing tendencies.... From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent." Sir Winston Churchill (from a speech given at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri on March 5, 1946).

Although Churchill was not the first to use the phrase "Iron Curtain", it became a popular naming convention for the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact countries throughout the Cold War after he introduced it in his speech.

The United Nations tries to raise the "Iron Curtain" after Britain, France and the USA have given up.

The threat of Communism posed by the Soviet Union was taken seriously by Canada's Prime Minister, W. L. Mackenzie King, who told the National Liberal Federation on January 20, 1948 that:

"So long as Communism remains a menace to the free world, it is vital to the defence of freedom to maintain a preponderance of military strength on the side of freedom, and to ensure the degree of unity among the nations which will ensure that they cannot be defeated one by one."

A similar sentiment was made in an address to the Canadian House of Commons in April of the same year as External Affairs Minister Louis St-Laurent argued that:

"The spread of aggressive communist despotism over western Europe would ultimately almost certainly mean for us war, and war on most unfavourable terms. It is in our national interest to see to it that the flood of communist expansion is held back." The belief that collective security was the only way forward led Canada to become one of the founding members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949.

Prime Minister W.L. Mackenzie King. Photo credit: Parks Canada

Maps

The Cold War map of Europe prior to the formation of Canada's No. 1 Air Division.

This map shows the four Fighter Wings and Headquarters of No. 1 Air Division in the mid 1950s. (https://coldwarconversations.com/episode63/)

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization

Following the Second World War, relationships deteriorated between the Soviet and Western powers. In 1947, the USSR set up a buffer zone...

The Birth of NATO - 4 April 1949

Canada had hoped to avoid sending troops to Europe and believed that providing weapons, equipment and aircrew training (in Canada) would be a sufficient contribution to NATO. The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 and the subsequent involvement of communist China changed everything. After much debate, Canada eventually agreed to send an air division of 12 fighter squadrons and an Army brigade group to be based on the European continent.

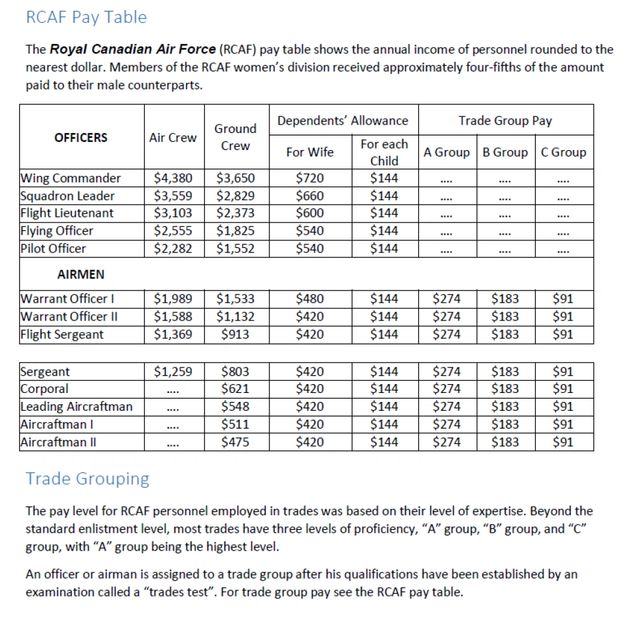

This would prove to be very challenging as military forces at the end of the Second World War were quickly demobilized and numbers were substantially reduced. The RCAF went from a war-time high of 215,000 personnel (including approximately 17,000 in the separate Women's Division) to a total strength of roughly 11,569. The lack of defined career policies for the post-war RCAF and the availability of quality civilian jobs led many of the most highly desired personnel to leave. Pay rates were unfavourable in comparison to even the lowest civilian jobs. For example, an untrained Aircraftman made $50 monthly if living in quarters or $95 if living off base compared to $147/month for an untrained labourer in Vancouver.

RCAF pay rates in effect in 1946

(Lest We Forget Information Package Second World War, Library and Archives Canada)

The situation with aircraft was just as bad. Wartime aircraft were unsuitable for Canadian defence needs due mainly to their extensive usage during the war and the fact that they had become technologically obsolete. The RCAF only had 124 of the 676 aircraft they wanted in 1946, the majority of which could only be used for training and transport duties. With shifting economic priorities, the government was not willing to spend any money on new aircraft, however the government was able to obtain 183 deHavilland Vampire jets from Britain as partial payment of their wartime debt to Canada. There was no fighter or bomber capability at all until Vampires were received in 1948. Unfortunately, these single engine aircraft did not have the range, speed or firepower needed to protect Canadian airspace and they soon became obsolete.

This situation would soon change though as Canadian companies answered the call to build jet fighters to outfit the air division. Canadair Limited of Montreal produced the F-86 Sabre under licence from North American Aviation while Avro designed and built the CF-100 Canuck. As the Cold War progressed, these aircraft would be replaced in 1962-63 by the Canadair built CF-104 Starfighter (again under licence).

.jpg/:/cr=t:6.69%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:76.92%25/rs=w:1240,h:620,cg:true)

Despite its limitations, the deHavilland Vampire introduced RCAF pilots and technicians to jet aircraft technology.

Screaming Jets

Production Ramps Up

This video from the National Film Board's, "Canada Carries On" series, highlights the production of the Canadair-built F-86 Sabres in their factory near Montreal, Quebec as well as the design and production of the CF-100 Canuck.

The Dawn of the Jet Age

Learn more about RCAF activities in the early Cold War through this on-line documentary.

A major recruiting drive begins...

The issues with pay, terms of service and a lack of accommodations and training facilities hurt recruiting efforts between 1945 and 1949. A major push to recruit men and women finally began to pay off as the period between March 31, 1950 and March 31, 1951 saw the RCAF Regular and Auxiliary force strength increase from 19,643 to 25,566, more than a 25 percent increase in just one year. By the end

The Canadair F-86 Sabre

Sabre Mk 2

The Sabre Mk 2 was the first variant to be mass produced at Canadair Ltd in Montreal. The RCAF received 290 aircraft between 1952 and 1953 with the majority being sent to newly formed fighter squadrons in Canada where they prepared to deploy to one of four fighter Wings at the Air Division in Europe.

Another 60 Sabre Mk 2 aircraft were sent to Korea to be used by the United States Air Force (USAF) in 1952. Twenty-two RCAF pilots flew combat missions in Korea on exchange duty with the USAF. In the photo is Squadron Leader (S/L) Eric Smith, DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross) on exchange in Korea.

Sabre Mk 4 and Mk 5

Canadair built 438 Sabre Mk 4 aircraft but the majority were sent to the Royal Air Force (RAF). A small number were temporarily used by the RCAF but they were too similar to the Mk 2 to justify replacing the older version.

The Sabre Mk 5 was a great improvement over the Mk 2 as it featured the new Canadian built Orenda 10 engine and wing improvements that made it fly higher and faster. There were 370 Sabre Mk 5s built in 1953-1954 and the bulk of them were flown to Europe by the No. 1 Overseas Ferry Unit (OFU), a special unit created in 1953 just for that purpose.

Sabre Mk 6

The best Sabre ever built was the Mk 6 version with the Orenda 14 engine. Canadair built 655 of them between November 1954 and October 1958, 390 of which went to the RCAF. Again, the majority of these went to No. 1 Air Division via the OFU. According to Larry Milberry's 1986 classic, "The Canadair Sabre", in their three years of operation between February 1954 and June 1957, the OFU safely transported more than 800 Sabre and T-33 Silver Star aircraft to the Air Division.

Obtain your own copy of the book for $40.00 plus shipping by emailing nbamdirector@outlook.com.

Sabre Mk 6 of 422 Fighter Squadron

The CF-100 Canuck

Beginning in 1956, one squadron of CF-100 Canucks was sent to each of the four Fighter Wings in Europe to replace one of their F-86 Sabre squadrons. This was done to provide NATO with an all weather/night fighter capability as no other aircraft in Europe was able to perform the role at that time.